A good way of bringing people and things together is to think of everything as an instrument. The music thinking framework allows you to think of all your different work tools, templates, or canvases as instruments. This is an effective way to bring collaboration into the workplace the same way musicians do it.

Join Tony Martignetti as he talks to Christof Zürn about his new book The Power of Music Thinking and some of his work-live moments in his career. Besides being an author, Christof has been in multiple roles like creative director, design thinking coach, service designer, facilitator, and musician. He is also the founder of Creative Companion and musicthinking.com. Learn more about the music thinking framework and how it can help leaders in their job. Discover more about how musicians work and some work-life cues.

Listen to Podcast episode #160 of the Virtual Campfire with Tony Martignetti

Transcript (automatic) of the podcast plus some personal pictures

It is my honor to introduce you to my guest, Christof Zürn. He is a seasoned professional in multiple roles like creative director, design thinking coach, service designer, facilitator, and musician. He developed tools, training, and workshops to inspire people to think from different perspectives to understand, innovate, and collaborate.

He specializes in competing individuals, teams, and organizations to move from iteration to innovation to transformation. His book, The Power Of Music Thinking, is due out shortly in the US but is available outside the US. He is the designer and the author of the book. That’s something that you don’t often read. He lives in Nijmegen, the oldest city in the Netherlands. It is my honor and pleasure to welcome you to the show, Christof.

I’m excited to be here to sit with you around that campfire.

It’s going to be a lot of fun. We’ve got the fire started. We’re looking forward to digging into your story and journey to where you’re making such a huge impact in the world. I don’t have the book in hand yet, but I can’t wait until it arises on my doorstep. It’s been pre-ordered. I’m looking forward to that. We’re going to spend some time uncovering your story through what we call flashpoints. These are points in your journey that have netted your gifts in the world.

We’re going to have a lot of fun digging into the journey. As you share your story, we’ll pause along the way and see what themes are showing up. I’m looking forward to this as I love the work that you’re doing. The audience is going to be thrilled to read some of your insights. With no further ado, I will pass it on to you. You can start wherever you would like.

We talk about music and music thinking. When people ask me, “What’s your background?” I have to think for a few split seconds about where to start. I start very early. I’m born in an entrepreneurial household in the South of Germany. My parents had a joinery. I’m a cabinet maker. I am named after the founder, the father of my grandfather. My grandfather gave the company to my father. My father made it bigger in the ‘60s and specialized later in making pharmacies. You have to understand that pharmacies and the in Germany were like the living room of the pharmacist. It was more of wood and everything instead of something clean.

I learned to see, feel, and experience that organization from different times. Much later, while writing my book and thinking about how I work, I realized, “This could have been influential on your life.” We sat at the lunch table in three generations. My grandfather was a joiner. My father was a joiner and also an entrepreneur. He expanded and came up with new things. He was an innovator. My mother I would say was the organizations HR manager. We also talked about the company. As a kid, I do not understand this because everything there is something else.

You thought, “It’s again about this.” Later, I decided to do my apprenticeship and then learned the craft in the company. I realized that all these different perspectives are on the same thing. I’m sitting at the lunch table with the C-Suite, and five minutes later, I was working together in the dirt and noise with the people from the workers union, and go on like this. It was interesting that some ideas, when some say, “This is like this,” then I thought, “I heard three versions of this.”

I also worked on and then also went to the build-up. We first built everything in the workshop, and then you drive wherever it was. It was in the whole of Germany and Austria, then in Switzerland. You drive for 5 hours, and in 1, 2, or 3 weeks, you have to set up everything. You have to do it with the client. You understand the client of the client, the organization, and the ups and downs. This is my start in trying to understand organizations. That’s the most important for me. I’m still curious about when I get to work as a consultant, a service designer, or how you name it. I want to understand, “How do they work? How many perspectives are there? Where’s the challenge?”

There’s something about what you shared which is interesting. This is your first immersion into design because people may not think cabinetry is a labor-intensive effort. You must think ahead of the actual building and what it looks like in the client’s spot. Is it going to fit? Is it going to have the dimensions? There is a lot of thinking that goes into that. The organization became immersive for you because this is your family. It doesn’t go away. You become immersed in this company. I assume that this becomes something you almost live and breathe because it’s your family.

What I liked so much is sometimes, when we had to get out and set up the whole pharmacy, people didn’t know who I was. You don’t tell everybody you come with a team of five, and people don’t ask you who you are. It was interesting to get an extra view, on the whole, let’s call it brand because, and to see how different people experience the same thing. We talked about the book. It has a lot to do because I make the difference in experience in the music thinking framework, whether it’s a product service experience, a brand experience, or an organizational experience.

All of the three are connected. Everything is connected. Music or music thinking is not just a metaphor, but more of an analogy to dive in to later see how you work, where you work, and the people with who you work together, but it’s also some systemic organization. In that sense, it always has to do with people. That’s interesting.

I’m dying to learn how you leapt out of the cabinet world or the joiner field into your next endeavor. What happens next after you decide to move on?

When I was ready and had my certificate, I got the call in my time to join the German Army like everybody has to do, but I refused. That’s what took so long. I did my civil service in Psychiatry. I’m working with mentally and psychic persons that were ill because this was something that I didn’t know. I have to thank my mother because one of the most quoted quotes from her was, “First, you learn a craft, and then you can do whatever you want to do.” After my civil service, I concluded that I knew how I could work with my hands, and I wanted to go in a different direction.

First, you learn a craft and then you can do whatever you want to do.

I studied Philosophy, Musicology, and History of Art. That was a heavy part and also, BTW we had 100 FTEs in the company. It was also clear if I stayed, I would be somewhere in the management. You can’t work with your hands if you’re a bigger organization. I was trying something else without knowing this or reflecting on that. That’s how I turned to Philosophy and Musicology. That grabbed my attention.

Later I realized how many people there were disappointed that I went away. Maybe that’s too hard to say, but most people didn’t see me as a person, but they did see me as a functional role. I disappointed them more with the perspective on me instead of me. That was something I didn’t know because I changed my perspective. I understood, “That’s how they see me. They don’t see me like I am to see what’s around me and all my context.” That was interesting.

I love what you just said because there’s a thing about it that is important. We often get wrapped up in the perception that people have of us based on titles or the roles we play, but in reality, that’s not what doesn’t define us. It’s not who we are. It’s what we do. I love getting out of the boxes of definition. Once you realize you’re so much more than defining yourself, it’s a powerful perspective change.

This was a pivot.

I love the decision to go into the space. It is interesting because most people would say, “What are you doing? How will you make a living going into this Musicology and Philosophy?” Most people would shy away from this industry or at least a field of study. They would say, “Shouldn’t you be studying Finance or Medicine?” I’m sure you had many naysayers saying, “Are you sure you know what you’re doing?”

There was one moment. When I told my parents I wanted to study Philosophy, I wrote a letter home because I was travelling. When I came home, everything was a little bit icy. Once I sat with my mother in the car, I said, “Didn’t you get that letter?” She said, “Sure, we did.” I said, “And?” She said something that made me think, “If you have this in your head, I can’t get it out of it.” I thought, “That’s also interesting.” Sometimes it’s also too to dare to do something. People think, “He can do this. He might also do something else. If he wants it, who am I to fight with him?” And there was still hope that I would come back. Maybe that’s also a part.

When I studied, and during the vacations, I worked. Sometimes I worked at home. Sometimes I worked at the assembly line of Audi to get this experience. I was collecting different experiences in working and maybe also a little bit organizations, but I was interested, “How is the car made? How is this different?” I was responsible for the right top part. Everything was moving and how people were doing this. I also work in record stores and a lot of different jobs, but this was just for money.

It was also free because you get the money for what you work. There was no long contract like this. I like this to earn money and also to get more experience. My horizon was getting bigger. I thought, “Maybe that’s my real driver, not just the curiosity, but the curiosity to not just to listen, get out, try to understand and make sense of different things that you don’t understand yet. Maybe that’s the most important part. “

There’s something about what you shared, which is cool because you are collecting information through all these different endeavors. Collecting information, then you figure out what you do with it all. Eventually, you start to take the dots and connect them through your work later in life. Being open to exploring these different paths is powerful. Some people say, “I would never want to do that type of work. Why am I wasting my time?”

If you go in with an open mind, you can see there’s value in working in a record store and doing even cabinetry work. There’s nothing wrong with any of that, but the reality is you may think, “That’s not what I want to do.” There’s value in every endeavor as long as you take the perspective of, “What can I learn from this? What can I take from this experience?” What I’m taking away from what you’ve shared so far is that you’ve collected many eclectic experiences but are also powerful in the curation of your life.

In that sense, to react on eclectic is not eclectic because if you connect the dots, they are parts of a system. If you disconnect the dots, they feel eclectic. That’s also very musical.

Here you’ve gone into this field, but this is not an easy thing. What is the profession that bubbles up? Before I get too far along, you said you’re a musician. What type of instruments that you play?

I like to play a lot of instruments. My curiosity goes very far. If I have to pick one, it’s the saxophone. I’m a saxophone player. I’m also into the ukulele. I have a lot of guitars, but the ukulele is nice. I take lessons in shakuhachi. You also could say, I can’t make a decision, but the decision is to play all of them, and maybe not all of them at the same time.

That would be crazy, but I like that. The decision is not to decide but to allow it all to come together.

Let your curiosity drive you – your curiosity to understand and make sense of things that you don’t understand yet.

Maybe that’s the central theme. I sometimes realize if you’re trying to play something on one instrument and come to a border where you say, “I have to rehearse that part.” Sometimes I switch to another instrument, and there it works, then I go back. I like changing the pool, then coming back and seeing the bigger pool. You have to decide on where you are at the moment. That’s something I like very much if you know a lot of instruments, you don’t necessarily have to play them well.

For example, if you compare a piano, it’s easy to play or get a sound out of it and hard to master. There are instruments like the shakuhachi that are hard to play and master. That’s interesting to understand what an instrument is. I also suggest this to all the leaders. Every leader should at least try to play an instrument if we look at big leaders, Richard Nixon, who was a piano player. Bill Clinton played the saxophone. Mastering an instrument is communication on one part, but on the other, it’s also something you must do by yourself as a leader.

It’s not just pushing the button. It’s also for you as a person to find something where it’s hard and not sports. In sports, when you’re getting older, you won’t be better and better. With an instrument, it’s something you get a lot of experience, and you feel how you are in the way you play. That’s maybe good advice from yourself as a leader when you want to.

Having not read the book but knowing a little about how this might play out, I even think about the entrepreneurial journey of when you start playing an instrument or a company. You’re not perfect. You’re not good at first. You don’t know what you’re doing. You have a hard time. You may even want to give up. You are like, “I can’t get these notes right.” The reality is if you’re persistent, patient, and continue to play. You find a way to keep on going. Eventually, you get into a rhythm and find that the notes start to come. After a period, you’re starting to almost do it without thinking.

That’s also the point in how I work, facilitate, or trying to help, or lead teams. There’s my curiosity part. I always would like to know everything and all perspective. When I started working, I forgot. I put it aside. Let me not lead you and try to validate what you already know, but be open to what happens and just later see, “That’s why it’s like this.” I liked that part, and that makes it on one part very intuitive. It only works if you are trained in the way to try to understand, have a big field, and not just fooling around. You are trying to make it profound, but then also be authentic at the moment and keep your ears open to realism.

I’m anxious to get into more of the concepts from the book and the work you do. Before I do that, I wanted to ask, is there another flashpoint waiting to emerge that got you further along your path, something you want to share along your journey?

During my study, I did different jobs. I worked for the radio and television, and then I got a job in the 1990s for a film production company. They did music films, life registration, Euroarts, and classical music freaks know the name. We did CD-ROMs at that time. You never hear edutainment and all these words anymore. The interesting thing was that they were about music, technology, and storytelling. How do you bring this into a new medium?

This was with the way how I worked and what I learned. Everything came together, and people wondered how much I knew about music and technology. It was the 1990s. I learned HTML while commuting in the train. It’s still going on, and then I came up with the idea of online interviews. I did my first online interview at the opera in Versailles with Daniel Barenboim, a well-known conductor, and interviewed him for the internet. That was in the 1990s.

There was no mobile or WiFi. This was pioneering and powerful in the 1990s of digitalization, with all these things like hypertext. For the people I might have lost with names or expressions like this, it’s just that if you click on a word, you get somewhere else. This was the concept in the ‘90s. I was right in the middle of it to understand what it could be and how you could use it for anything. Music was what was my driving force back then.

One funny anecdote to share was when we finished some of the productions. There was also the idea, o.k. “It’s over.” In the 1990s, we already felt the CD-ROM was over. The question is, “What do you do then as a new media department?” Interestingly enough, I thought that I get laid off, but it was the other way around. They said, “You’re the one we’re keeping because you’re developing. You always come up with something new.” I was paid for my curiosity. Maybe it’s not just curiosity. You also have to get your hands on it, so the craftsman comes through on that part. It’s not just knowing something better. You have to try it out, get a feel for how it works, do it, and then help others doing it.

For me, it was something. I then switched from film production to an agency – a different world. It was not about the content I was fond of anymore, but all the patterns. I saw patterns everywhere, went into an agency, and did the pitching. For me, this was natural. That was something that I realized. That’s because you always try to connect stuff. You see stuff quicker because you see the pattern already.

That was something for me that switched from the film production or new media department in the film production to the agency world where you get a client of a client. There is a lot of pressure in trying to keep a team together to realize it because you can’t do it. You can’t program everything. It was something powerful and important. It was not about you. It’s about the team. You can make the difference alone. You may be for a day or half a day if you have to present something. You’re out of that business if you’re not a team player.

I always think about how people talk about passion and say, “You can’t just follow your passion and expect to find the things to have things work out.” In some sense, the things that light you up are like the tree, and then the branches are the things that you pivot and move into. They extend beyond. When one branch dies off, you can move in another direction, grow, and expand.

When I hear you talk about the ways you were able to make different things happen, it is because you’re always open to new opportunities and things that showed up. You didn’t see, “The CD-ROMs are going away. That means the end of my path.” It means you’re going to take another branch and then be curious about what happens next. I don’t know how to define what it is that your passion is, but there’s something at the center of this trait that is driving you down this path.

The way you listen to music you like is also the way you listen to other people.

Usually, I don’t use the word passion because it’s more about being independent in one way. That’s maybe something that I think about work relationships where I was in the leading position. I had to tell people sometimes what to do because they didn’t see it and then realized, “Maybe I should have done this differently.” Being part of a system sometimes depends on the company. You think, “I’m part of the system, but I don’t like the whole system. People see me again in a different light as I am.”This was important always to be open, frank, caring, and trying to understand.

That’s great about curiosity about people. Try and go, “Why are you acting like this? It’s about me, but what can I change so that you don’t have that problem?” That was good to learn. When people talk with you and want something different, it’s not always about you but their perspective. You can help them to change their perspective if you move. It’s not only that you had to have them move, but you can also move. People see maybe the background, backdrop, or something in a new light. That’s something that I’m interested in. In my world, that’s the analogy between real-world business society and everything in the context there and the music that is nearly in every society and very different.

I always talk with companies and say, “I have an assumption. My assumption is the way you listen to music. The music you like is how you listen to other people, your business, or your client. That’s an assumption. I don’t know if this is true. I’m not a scientist in that part, but what do you think?” You see, people think, “How do I listen? How do I make connections with the music? Do I go to the opera because it’s about the nice clothes, the people I meet there, the champagne, and the break? Do I love to sit there and hear something I don’t hear on the street?” Fill it in it. It’s also like going to a heavy metal concert, an Indian raga, or the Outbacks in Australia. Everything is interesting. The question is, “How do you listen?”

There’s a sense of questioning at the deeper of why and how each individual connects with that thinking around what we’re doing with organizations. It’s interesting. We’ve got this natural transition into my next question, which is to tell us more about the book’s premise. What do we look forward to? What will I get to read more about in the book that you can share a little taste of here?

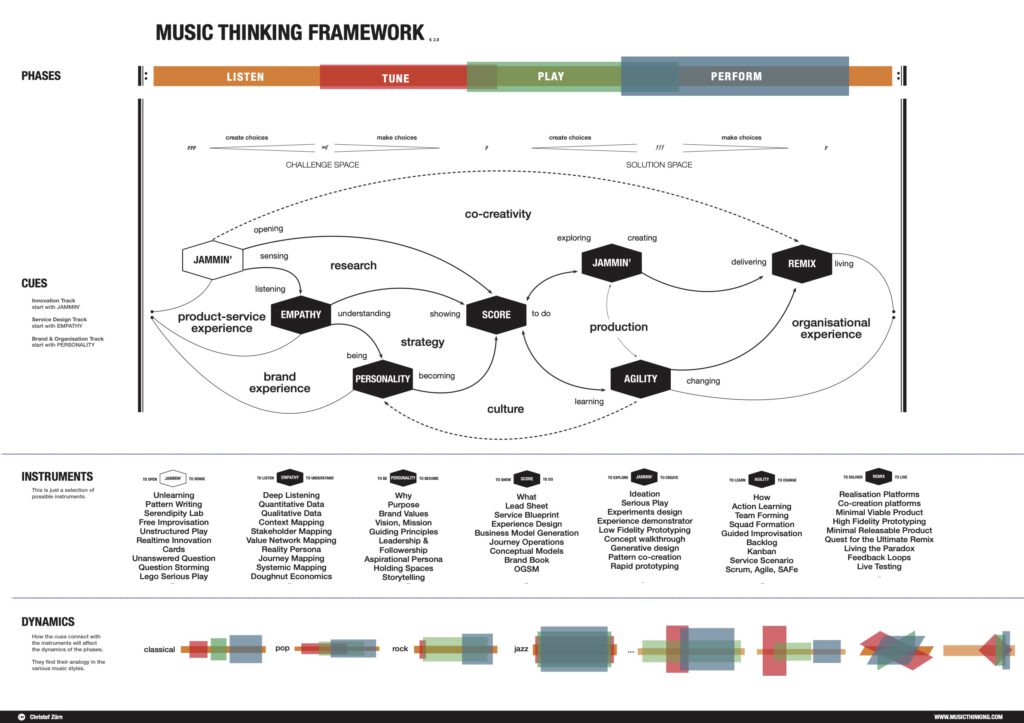

It starts with the framework. If you go to MusicThinking.com, you can download the framework and everything described in the book. You can download and use the PDFs. The framework was the thing that I tried to bring all the ideas I encountered. I also work in design thinking. I was Chief Design Officer at the Design Thinking Center in Amsterdam. I had a lot of experience in different fields. I try and go, “How can I bring this together so that they can at least connect all these silos that we have in a company, or at least that people get the feeling that there are different silos? ”

I came up with the music thinking framework. I did one thing. When you work in design thinking or in lean (start up), you work with different tools, templates, or canvases. The musical way to look at this is like: ‘everything is an instrument’. The business model canvas is an instrument. Persona is an instrument. Customer journey mapping is an instrument. The question is, “What do we want to play?” What instruments would be natural to fit together in the way we need?

That’s like a composer who comes up with a new idea. That’s the basic idea. I don’t say music thinking is the next big thing. Music thinking helps all the other things to bring together. In the Design Thinking Center, people in my workshops sometimes said, “Why should I think like a designer? Can’t they think like financial experts or programmers?”

I said, “You’re right,” then I switched and said, “Do you guys have a music department in your company? Can we use this as an analogy to bring you guys together? Let’s forget all the words and try to get how we can connect things.” I don’t teach people music. That’s not my job. I try to find out how they listen. It’s not about me. It’s about them.

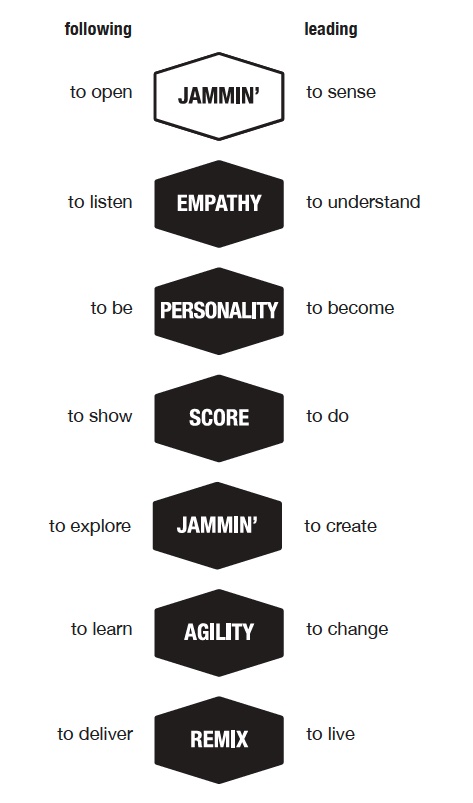

If they listen from a certain perspective and other people from another, I try to reveal this and bring them together. That’s the basic idea of music thinking. To make it very practical, I came up with what I call: a cue. You would see that on a stage when the musicians are together. They’re nodding and saying, “Now we go to the end.” That’s a cue. It’s like a sign.

There are six cues in my work life when I work together with companies. One is around empathy. It’s listening and understanding. By listening, I mean getting all data. It’s listening with your whole body, qualitative-quantitative information, and everything that can come in. Another one is the score. It is like a high score, but also like a musical score. That’s interesting because one score is about showing. That’s how far it is, and the musical score is about doing. If you take a symphony score when you’re the trumpeter, you must wait for certain bars because it’s not your moment to play. It’s exactly written down.

I thought, “This concept could help companies to make clear. I want to show that it is like a vision of the company. You can like the vision, but it doesn’t mean what you should do. We have to translate this also in a to-do.” So, we have empathy and score. another one is something like jamming, which means exploring and creating. You can also start with creating and then exploring. It doesn’t matter. You need both of them. It’s not just delivering and working on something. We need something like a remix.

Like, It’s 8:00 a clock. The whole concert room is filled. The curtain goes up, and you have to play. There’s no excuse. It’s showtime. It’s performance. That’s the remix cue. Then, we have now 4, but I was missing 2, and 1 was personality. Every company is in the middle of it. It’s like to be and to become. You’re always where other people say who you are and in a situation where something else changes. You want to go somewhere, or people force you.

Many designers or creators have problems because they listened to the client well and came up with a fantastic, innovative idea that goes right into the drawer when the company says ‘no’. If you don’t understand the organization or the organization’s personality, you can do as innovative as you want to be, but it will never help. Personality was varying the second input. You can see the whole framework of an analog synthesizer, getting output and input.

Output from empathy is what people need. The output from personality is who we are and that goes into the score. As an output, you have jamming, the creativity part, and the agility part (learn and change) because we have to understand the score. We have to learn the score. Or, we might need different people to play the score. You might get different dynamics when these six cues are played together with different instruments. The downside of the framework is it looks complicated, but the upside is, that it is complicated like life. If you try how it works, then you understand how it works and , “That it is much better than having a simple model that never answers my question when it’s getting interesting.”

Simplicity and complexity are best friends.

It’s dynamic in that way. I also write in the book that simplicity and complexity are best friends. As a company, when I focus on simplicity for me as an organization, I know that the complexity will be on the other side with my client. I have to understand how to make it simple for the client and sometimes make it complicated for the organization, but this will keep me going.

That’s why there may be a lot of words, and people can fill it in as they want. That’s the center of the idea here, the six cues. One cue is double, but that’s for later. All the cues have two sides. One of the sides is like ‘to be” and ‘to become’. One is a follower, and the other is the leader. To be is following because I’m following what I already do and how people see me. To become is leading to show what’s happening. It is following and leading. All the cues have both sides. It’s not one or the other side. You need both. It sounds complicated, but it’s not more complicated than a medal with two sides.

This is an interesting framework. It’s something that many people can use to change how they’re showing up, and organizations are running. I can’t wait to dig into it. One of the things that we’ll share a link to is the book. People can pick it up on your website. People can dig in and learn a bit more. I’m grateful that you shared that overview of this situation. I appreciate it. Before we wrap up, I have one last question to ask you. What are 3 books that have impacted you and why?

When I thought about it, I was pretty surprised which book I picked, and I picked Being Digital and Nicholas Negroponte. Do you know this?

It’s never been mentioned on the show, but I have heard of it before.

1995 was the year when I started with the New Media Department, the film production. That’s because I thought, “I might pick this book.” I read a few things and said, “This is so great.” I love to read something in their time from our time. Now in 2022, the book is 27 years old. Please read it with the knowledge of nowadays and with your imagination of them. Maybe some of the readers were even born on that day. That’s something I want to give.

There was another one. It’s Neal Stephenson’s Seveneves. I’m a big fan of speculative fiction. I read everything from William Gibson and Neal Stephenson. Seveneves is the one that I pick. It’s not the first. Nowadays, we talk about the metaverse, but it was written and explained in his book Snow Crash at the beginning of the 1990s. That’s also when I started with digitization. Seveneves is also a palindrome. You can read it from back to forth. It’s a marvelous story that goes above time and above imagination. That’s the second one.

The third one is from R. Murray Schafer, a Canadian musicologist and musician. It’s called The Soundscape: Our Sonic Environment and the Tuning of the World. These are the three books. They go well together. The sounding of the world is the well from acoustic ecology and trying to understand how our hearing or listening changed. Sometimes we make snapshots and pictures. If you had done this 10, 20, or 30 years before, we would say, “There once stood a house here.” It’s the same with sound. If you’re in a certain place and would go now 30 or 40 years back, it would sound differently. The sensitivity of listening is something I like.

I love how you described them because it adds a lot of context as to why we should read them and how we should read them. I could talk about this stuff all day long, but I can’t thank you enough for coming on the show and sharing your stories and insights. It is powerful.

Thank you very much, Tony. It’s great to share all these with you.

Before I let you go, I want to give you an opportunity to share the best place where people can find you.

Please use LinkedIn. And, if you connect, please provide 1 or 2 sentences why. For example, you read this interview “I love context.” 🙂

Readers, thank you for coming on the journey. I know you’re leaving with so many great insights.