Did you ever ask yourself, how could I pass my knowledge and my experience to someone else? In the current speed of innovations and agility, it is quite a challenge to transfer knowledge. Making an online course is not for everyone, and telling what you are doing is not sufficient for real knowledge transfer. Here is another approach that I can recommend.

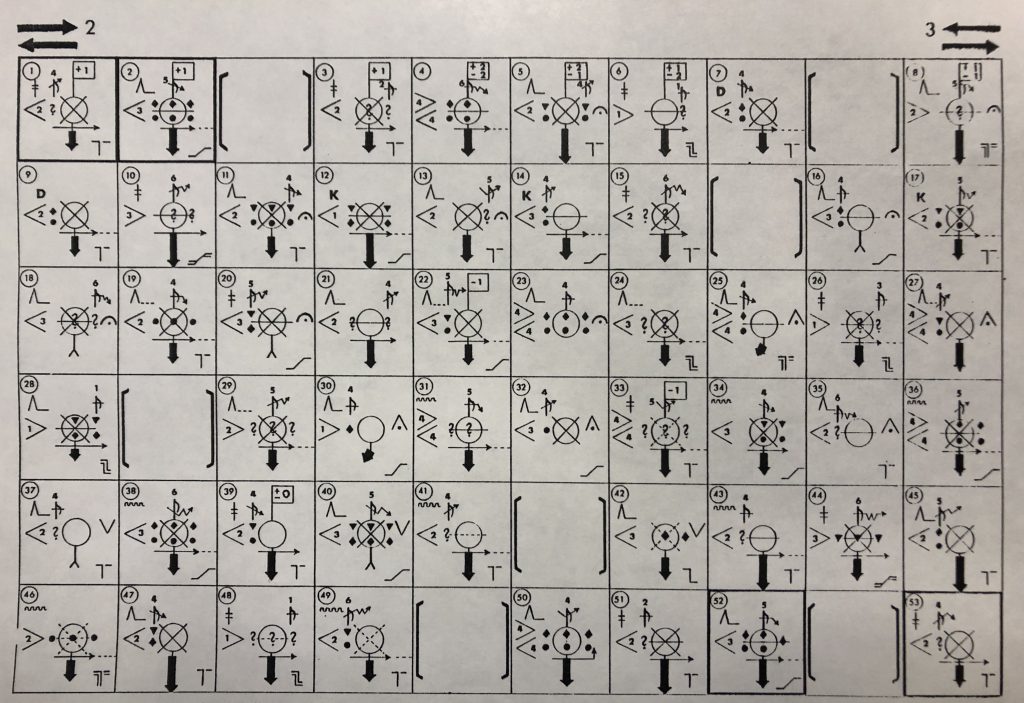

When the German composer Karlheinz Stockhausen (1928-2007) had a break on a beach in Italy, in 1963, he composed a new piece called “Plus-Minus”. It was a piece of music of a totally uncommon kind. Instead of just notes for musicians to play, “Plus-Minus” contains a completely new graphical notation. The notation was never used afterwards, not by him, not by anyone else: a unique one-time composition. At a closer look, it turns out to be even more unique.

“Plus-Minus” is the result of a retrospective. Stockhausen must have asked himself, at that time in 1963 at the beach of Palermo, looking back to the 42 compositions he had made since 1950: how do I compose, what are the structures I use, and how could I have others make new compositions based on the same structures? In other words, what are the structures of my own musical thinking?

A set of instructions meant to make a score

Plus-Minus is not only a different notation, it is not even a regular music composition. Plus-Minus is a set of instructions meant to make a score. It is a meta-composition: it is a score for a composer to make up his own composition based on the instructions by Stockhausen. A unique piece of art in the post-war period that inspired many.

I have always found this an inspiring idea. It is a designer’s idea, not only valuable for composers and musicians but for every kind of designer, be it art, engineering or organisation design. It is a way of reflecting on one’s own way of working and make it reproducible for others. Everyone could ask herself: what are the structures of my own thinking, and how can I express them in such a way that everyone else could make her own version out of it?

Expressing these structures in a meta-language can be challenging.

Meta-languages must conform to two principles

Meta-languages must address a non-meta-language that can be understood by the target group. Stockhausen e.g. refers to music notes, his target group being musicians. A meta-language for IT programmers should refer to computer language concepts, a meta-language for information architects should be information concepts, a meta-language for furniture designers should be furniture constructions.

Meta-languages must define ranges of freedom for deliberately chosen aspects. Stockhausen refers to a “musical sound” in Plus-Minus and leaves the decision of what sound (musical instrument) this should be completely free. The structure, however, of how these sounds are repeated during the piece are dictated more strictly.

Meta-languages are quite common in IT, where programmers and architects define “domain languages”. Meta-languages could be applied in a much broader context, however. Also, UX designers, service designers and information architects could define their own meta-language.

A beautiful advantage

Defining your meta-language is a form of reflection with a beautiful advantage: it enables others to use your thinking structures in their design. You need some practice, but it is a very effective way of transferring your deeper knowledge and experience to others.

So, what is your meta-language?

Alcedo Coenen

Enterprise Architect with an M.A. in Musicology

Some inspirational links:

Ming Tsao about Plus Minus

Plus Minus No. 14 (video)

Original score available at Universal Edition

Music Thinking Framework with SCORE as one of the cues

You might also like this podcast

This episode is about Innovation patterns and improvisation in organisations. Today, my guest is Prof. Dr. Wolfgang Stark – a teacher and researcher specialising in organisational and community psychology and visiting fellow at the Vrije Universiteit in Amsterdam.

We chat about the difference between learning and organising and the meaning of improvisation in business and society. And we learn how patterns of success translated to a card deck can be used in co-creation, innovation and change. In the end, we hear about the innovative invention of ‘the music box on a garden fence’ that started in corona times. Listen to Innovation Patterns.